C# Async for Slugs

Fun fact for you dear reader, I've not been programming for long, my degree was in Chemistry and though I taught myself a little programming during my degree I was mainly focused on Chemistry. This means I've been programming professionally for less time than C# 5 has been released.

This is why I've found tutorials so far for the Async/Await features in C# 5 (Net 4.5) to be a little lacking, they generally assume the reader has been writing async programs prior to the release of the features.

As a solution to this I've endeavoured to write a guide to async for miserable slugs like myself who have not had exposure to async prior to these keywords.

Demo Scenario

We're going to stick with a very simple console app available on GitHub to make sure all the concepts can be understood by a slug.

Our Program.cs main method is shown below:

public static void Main(string[] args)

{

SlugService slugService = new SlugService();

slugService.GetSlugs(generation: 1);

}

The GitHub version contains a lot more lines which allow the method calls to be timed with the built in stopwatch.

The Slug Service is tasked with retrieving the records of some slugs we've stored somewhere. Let's see what it does:

public IList<Slug> GetSlugs(int generation)

{

Int64 generationalPrime = primeFinder.FindNthPrime(50000 + generation);

IList<Slug> slugs = slugGetter.GetDataSlugs(generation);

foreach (var slug in slugs)

{

slug.FavouritePrime = generationalPrime;

}

return slugs;

}

Again, the GitHub version contains more code related to timing methods with Stopwatch. This method does the following things:

- Gets the favourite prime for this generation of slugs. (As we all know, slugs are huge prime number fans).

- Get the slugs from our storage medium.

- Set the prime for this generation of slugs.

The prime finder gets the nth prime for any n. It's written to be quite inefficient so we can replicate some external call or large calculation that blocks the program.

public Int64 FindNthPrime(int n)

{

if (n < 1) throw new ArgumentException();

List<int> primes = new List<int> { 2 };

bool primeFound = false;

int index = 3;

while (!primeFound)

{

if (primes.Count >= n)

{

primeFound = true;

break;

}

bool currentNumberIsPrime = true;

foreach (int prime in primes)

{

currentNumberIsPrime = index % prime != 0;

if (!currentNumberIsPrime) break;

}

if (currentNumberIsPrime) primes.Add(index);

index += 2;

}

return primes[n-1];

}

If you don't understand the maths just ignore it, suffice to say when you call this method with an input of ~50,000 it takes around 8 seconds to return a result.

Finally we need to get our slugs from our data storage. I've not actually implemented a persistence medium for this demo so the SlugGetter does this instead:

public IList<Slug> GetDataSlugs(int generation)

{

List<Slug> slugs = new List<Slug>();

for (int i = 0; i < 1000; i++)

{

slugs.Add(new Slug

{

Id = i + 1,

Name = "Slug" + i.ToString(),

Generation = generation,

CabbagesEaten = (i % 2 == 0) ? 1 : 0

});

Thread.Sleep(5);

}

return slugs;

}

The thread sleep in this method slows everything down so the program runs on a timescale which can be easily compared between runs.

The Problem with Synchronous Execution

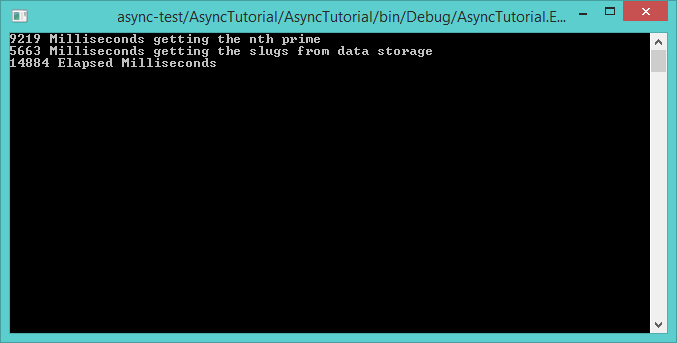

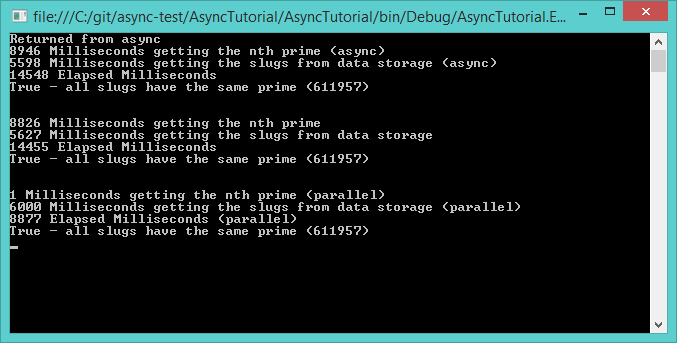

Running the program with the Stopwatch related lines included gives this output:

The total run time is almost entirely due to the time taken to calculate the prime and the time taken to retrieve our slugs. The rest of the program takes about 2 milliseconds to run!

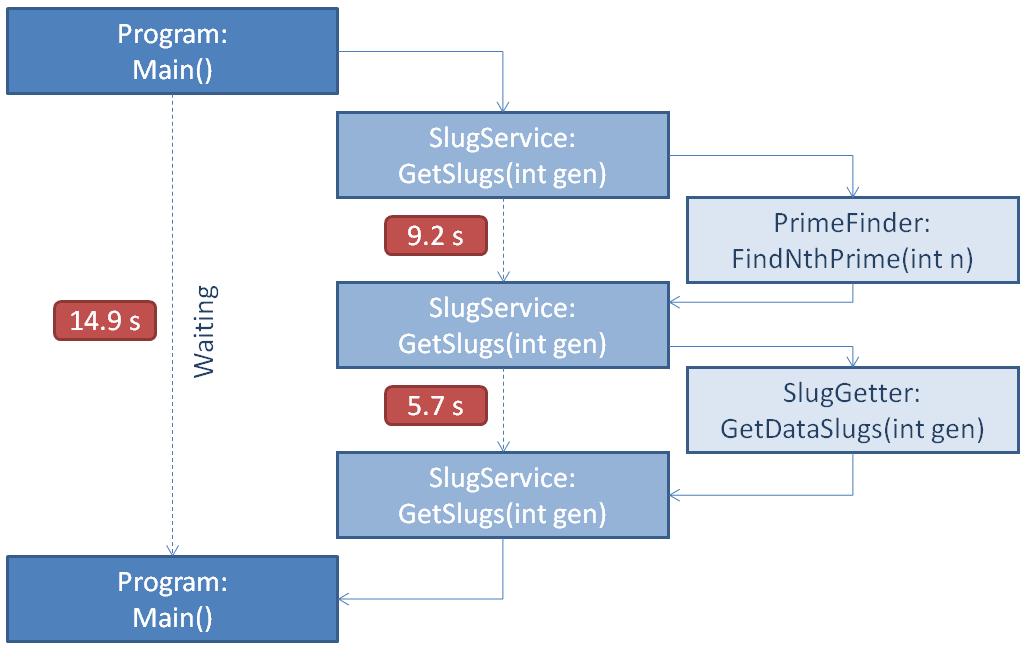

Unfortunately in the normal synchronous way of calling methods each method is run in turn causing our program to take a long time.

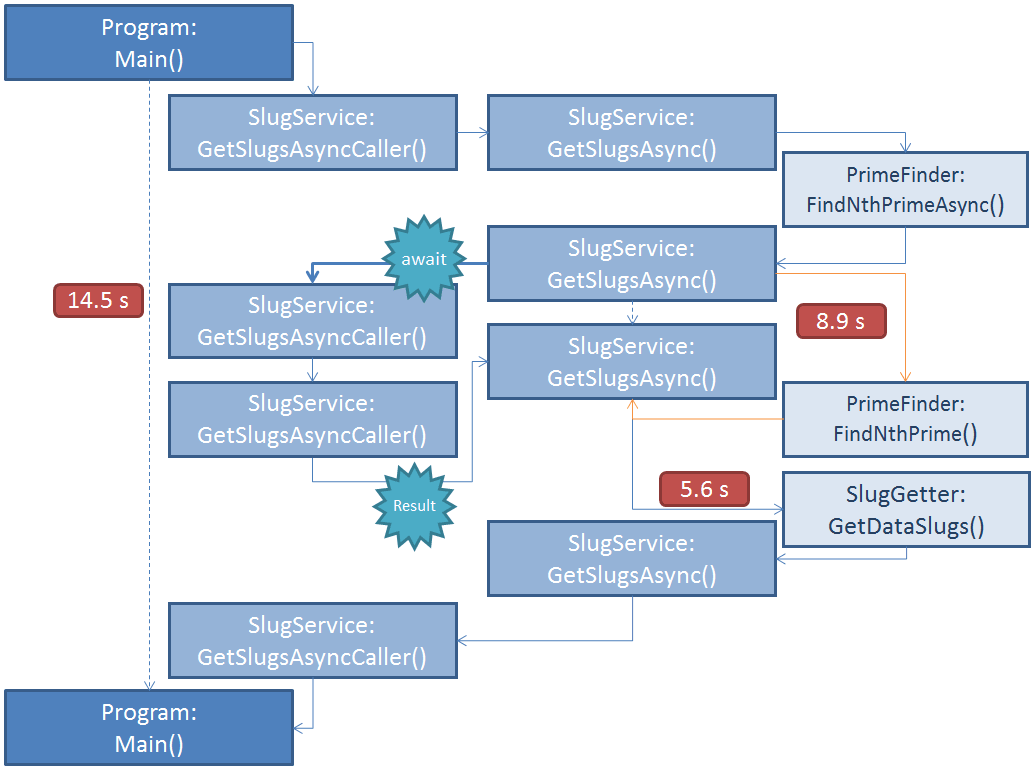

To visually illustrate the call stack I created this diagram:

By boosting the hardware of our computer we might achieve a more speedy slug retrieval (through a faster primefinder) however there's a limit to scaling up in this way. We need to move execution on to other threads so we're not being blocked by the PrimeFinder.

Parallel Execution != Async

This is the first conceptual hurdle for people new to C# wanting to learn about async and await. Since all examples of async use methods which return Task<T> it's easy to assume Task<T> is related to the async features.

Task<T> and related concepts in the System.Threading.Tasks namespace have actually been features of .NET since .NET 4.0. They form the core of the TPL (Task Parallel Library). We can therefore rewrite our SlugService with a parallel execution mode.

It would be nice if we could run the PrimeFinder on one of our cores in a worker task while the main execution ran the SlugGetter.

To create a Task for our PrimeFinder we can wrap our normal method in a new Task:

public Task<Int64> FindNthPrimeTask(int n)

{

return Task.Run(() => FindNthPrime(n));

}

Task.Run() instantiates a new Task object and starts it running, it is a slightly nicer version of the .NET 4 TPL Task.Factory.StartNew() however you should use Task.Run().

Our method call now returns a Task so in our slug service we need to change the result of the PrimeFinder call to a Task<Int64> object:

public IList<Slug> GetSlugsParallel(int gen)

{

Task<Int64> generationalPrimeTask = primeFinder.FindNthPrimeTask(50000 + gen);

IList<Slug> slugs = slugGetter.GetDataSlugs(gen);

Int64 generationalPrime = generationalPrimeTask.Result;

foreach (var slug in slugs)

{

slug.FavouritePrime = generationalPrime;

}

return slugs;

}

Where we call Task.Result the main thread blocks execution while waiting for the results of the Task. This means we avoid a Race Condition where we use our prime before it has been properly calculated.

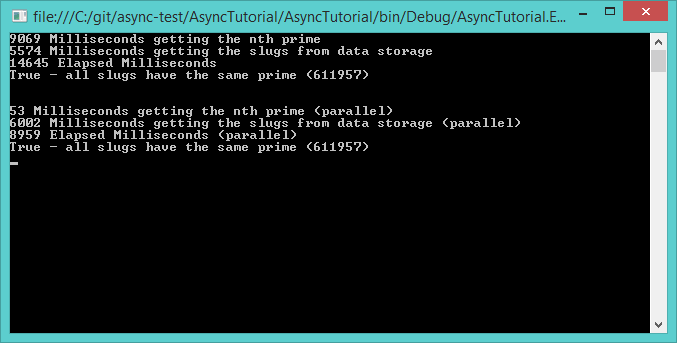

We will run the synchronous single threaded GetSlugs and then the GetSlugsParallel method:

As the results show, the run-time was almost entirely due to the time taken to calculate the prime (53 milliseconds was spent calling and returning the task). With the prime calculation taking place on another thread we were able to reduce run time.

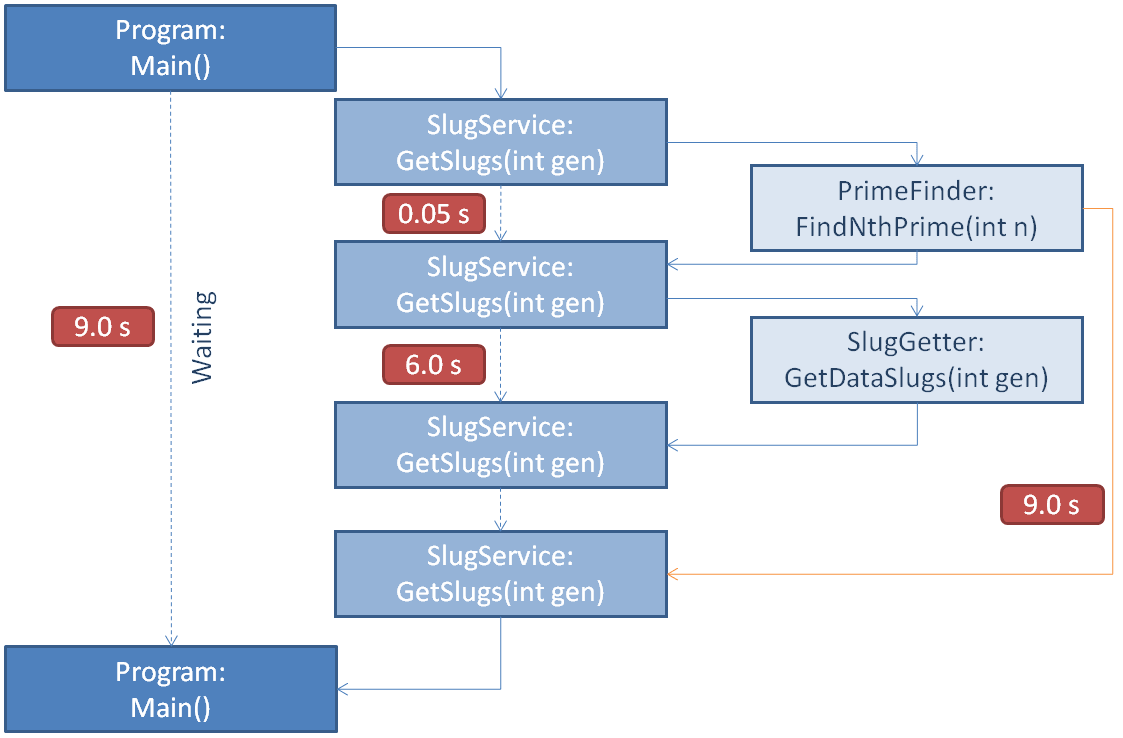

It gets a bit harder to illustrate this call stack. First SlugService is called normally and performs a call to PrimeFinder as usual. However this returns in 50 milliseconds and the main thread goes on to run the SlugGetter which takes 6 seconds to return a result.

In the meantime a worker thread (in orange) runs the prime finder which takes about 9 seconds to run. This is running while the main thread is running SlugGetter. Therefore rather than adding runtimes together as we did for synchronous execution we take the highest time (this isn't always the case but works for this example).

Time for Async

So we've seen how we can use parallel execution without the async/await keywords. Let's introduce them to our program now.

For our PrimeFinder we do not need a new method, we should avoid creating asynchronous wrappers over synchronous CPU bound methods.

In SlugService we create a method with the async keyword in the method declaration. Async methods must return one of the following return types:

Task<T>Taskvoid(don't return void from an async method due to exception handling)

This is achieved by changing the body of the method as follows:

public async Task<IList<Slug>> GetSlugsAsync(int gen)

{

Int64 generationalPrime = await Task.Run(primeFinder.FindNthPrime(50000 + gen)).ConfigureAwait(false);

IList<Slug> slugs = slugGetter.GetDataSlugs(gen);

foreach (var slug in slugs)

{

slug.FavouritePrime = generationalPrime;

}

return slugs;

}

This is a bit confusing, the method is declared to return Task<IList<Slug>> but the method body returns an IList<Slug>. This is because the compiler can be thought of as wrapping the method up into a Task behind the scenes.

We have used await in the body of the method to tell the async method to wait for the Prime Finder to complete. Also note the use of ConfigureAwait(false) after the call to FindNthPrime(), this isn't strictly necessary in a Console App but will help to prevent deadlocks in UI/ASP.NET code by ensuring the completed task doesn't ask for the original thread back. We also call Task.Run() on the method rather than in the method implementation as recommended here.

Because Console Applications cannot have an async main method we have to 'unwrap' our async call at some point. To do this I created another method in SlugService that main actually calls to, Stephen Cleary outlines how to do this properly for console apps in the link but I'm using it here to illustrate a point:

public IList<Slug> GetSlugsAsyncCaller(int gen)

{

var task = GetSlugsAsync(gen);

Console.WriteLine("Returned from async");

Thread.Sleep(1000);

return task.Result;

}

This time the console output looks like this where async is run first, then synchronous and finally parallel execution:

As the results show, the async execution (14.5 seconds) takes just as long as the synchronous execution. But we're dealing with tasks, what gives?

Async works in a quite different way to parallel execution and async execution is not necessarily parallel. Let's look at a call stack diagram that attempts to explain this (again the blue arrows illustrate the main thread).

This is all terribly confusing. Basically at the point the code execution hits await in GetSlugsAsync it returns to the caller, in this case GetSlugsAsyncCaller, this is illustrated with the thicker blue arrow. The execution of that method (GetSlugsAsyncCaller) continues. It is then blocked by the call to task.Result and the rest of the GetSlugsAsync method executes in the normal way.

Let's reiterate that; await returns execution to the caller and the caller continues to execute normally. Because we started the PrimeFinder task this executes in parallel while we're back in the GetSlugsAsyncCaller method which is why the Thread.Sleep(1000) in that method doesn't increase the execution time. However the actual GetSlugsAsync method isn't parallel with respect to the flow inside its body, the await is blocking since the PrimeFinder task must return a result at this point.

Purpose of Async

So the async/await doesn't give us any (parallel) execution time benefit inside the GetSlugsAsync method itself. It's nice to continue to execute the calling method for a bit but this is of limited use. The calling method generally needs the result of the method called at some point in its body and because waiting for the result is blocking we don't gain much benefit.

So what's the point?

Well, the console app example falls down because it is not a good use of async. Async is like a virus that spreads through your code (not in a bad way), it only really works where the full call stack consists of async methods, you generally lose any benefit when you have to call .Wait() or .Result on an async method.

Because you can't have an async main method in your console app (it would return control to the Operating System which would mess everything up / close the app) it's hard to demonstrate the advantages in this type of app.

It's most obviously useful in WPF and ASP.NET applications. These both allow the methods called to return an async method at the root level to the caller:

- In WPF the async method returns control to the UI loop on a call to

awaitin the code-behind, this means the UI thread continues to be active while the async task is processing. - In ASP.NET the async controller action returns control to the application pool threads in IIS. This means the server can respond to other requests while the original request waits for its task to complete, generally using async I/O operations such as file I/O. This has a lot to do with I/O Completion Ports. Therefore if we only have 50 threads in our application pool to respond to website requests we're not tying them up dealing with long-running tasks and they can more quickly be used to respond to further requests. This does not mean the request is returned to the client early, just that the thread is returned to the server while the request processes.

The actual way in which true async requests are dealt with in WPF and ASP.NET is different to how it was illustrated in this tutorial. In this tutorial an extra thread was used and blocked while the prime was calculated because this was a CPU calculation and not a good candidate for async. True async operations such as file I/O don't use an extra thread.

See the section titled "What About the Thread Doing the Asynchronous Work?" here. To quote from that: "[...] no thread is required for true asynchronous work. No CPU time is necessary to actually push the bytes out ".

Further Reading

This was a very simple introduction trying to clear up a confusing subject. Hopefully with the understanding you may/may not have gained from this tutorial you can go on to read more about async with the concept being slightly clearer.

Stephen Cleary is the expert on async in C#, therefore it's not surprising he features heavily in the below links and most writing about async/await: